"Born in 1967, Valencia, Spain

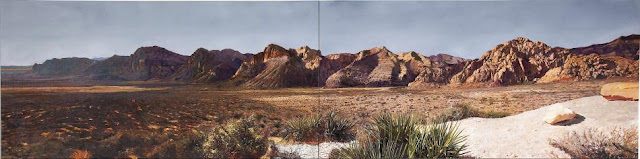

Las Vegas, Rangali Series. A Statement.

Las Vegas is surrounded by a bleak landscape—the Desert—where death is all that can be expected. In Rangali, in the Maldives, this immediate hostility is embodied by the Ocean. Both Las Vegas and Rangali are places where the most dangerous, risk-filled landscape directly borders the most favourable, pleasant environment, designed and built as a place where the vanquishing class can pay for peace of mind, for feeling protected and worry-free, for being without fears, while faced by the unfavourable, and in this case immediate, outer landscape.

Nothing to worry about, nothing to build, nothing to alter, nothing to fight against. Those who pay to cease being alert appear stunned, relaxed. They know they are safe in the eye of the hurricane. In the Maldives, this hurricane’s eye can only be grandiose. The landscape becomes an implausible optical effect by revealing itself as fully analogous to its graphic portrayals in the mass-media and in travel agency brochures. Those who return from a trip to the Maldives do not show any photos—What’s the use? We know the story. The images captured by visitors are a lesson or a demonstration: impossible to approach the subject other than as a post-card, as a photograph from a travel catalogue; no room for anything different, for improvisation or specific interventions; no hidden alleys or unexplored perspectives. Everything is given to us ready-made, definitive and predictable, already built and apparently indestructible. The number of focal points on the island, from which every “noteworthy site” can be seen, is limited and is conditioned by the system of roads and beaches. Nothing to translate, nothing to reformulate, a mirage. Both Rangali and Las Vegas are forgeries, ever-hated by those who miss the outdated criteria of authenticity.

In painting, realism is very easy, and so is the most extreme abstraction. I can reproduce anything, and I can do it very faithfully, as a camera would, avoiding any filter, any improvement or intervention. Despite their position as theoretical extremes, photo-realism and monochrome painting share a ceremonial taste for lethargy, for what is easy, for what doesn’t need to be interpreted or corrected, the mechanical, the industrial, for what turns us into a tool. In those two genres, both the process and the result can only be slushy and sticky, precise, gridded: we know it by heart, we have seen it ad nauseam. We could point to a certain continuity between mechanically painting a copy of a photograph and producing a flat monochrome surface. Two extremes that seem to converge.

I strap my camera around my shoulder, I let it hang by my hip, with a remote shutter release. I play the role of a neurotic, impotent prowler. This is Rangali. The Ocean is a few metres away, in the background, behind an artificial beach, strange and murky like the mossy marble slab of a grave. Here rises the extreme work of man, which feeds on men. There rises the primal landscape, devourer of men. Two extremes copulating. Like the tombstone and the grave. Through the camera lens, my character captures images analogous to those delivered by the ever-unexpected mirror on the column of a shopping mall; images of other bodies, or one’s body, this time immersed in the dialectics of the other, of the double. In those encounters, my character takes on the appearance of somebody who seeks to be liberated from initiative and anxiety, to surrender to the dominance of what is easy, and to be humiliated through the contemplation of the specific fragility of the sterile.

Each painting conceals a bomb behind its stretcher. That’s why I expect the viewer will not feel comfortable. It is not a game, it is not a question of finding anything that may lie in the painting. The paintings in the Maldives series speak the dangerous kitsch language characteristic of the taste of a certain social class. The members of this social class appear on the paintings, they will see themselves reflected like in a mirror, static, like effigies of themselves. The appear relaxed and happy, like a tragic summary. In some way, they don’t know what the non-happy think, their exclusiveness has taken them too far.

I have used two kinds of canvas in this series. One absorbs the paint more than the other, and the former lacks the dazzling white primer of the latter. The least absorbing one forces painting by jerky strokes, while the white primer makes the brush slide in a more flowing manner. I paint mechanically, like a brainless person. I invent games to stay alert, to keep my attention on the canvas during the painting process. I can paint and consider definitively finished some areas the size of a typing sheet of paper, that are far apart, while the rest of the canvas remains empty. I can make a grid on one or two canvases and pretend that I paint the pictures following a geometric pattern. I can paint the canvas like someone who writes a story, from left to right and from top to bottom. Anything to avoid the tremendous anxiety I feel from painting like a machine.

The videos that accompany my series set a course, that of rejecting the present, the course that protects us from our worst fears and makes us follow in the footprints of an uncertain order. My character carries out disciplined crossings, without needing to pause, without intending to penetrate the world, deliberately omitting crossroads and options. They are obsessive hikes, similar to those of Harry Dean Stanton in Paris, Texas, or those of Burt Lancaster in The Swimmer. Animals without a way out, social corpses stripped of any prestige that run away from the need for action, thanks to an excessive task that places them far from turbulence. These strolls always border the danger zone, the Ocean, that no-man’s-land where a naked, persistent immersion would lead to death. The perimeter of Rangali Island can be walked in half an hour, like most of the Maldive Islands. "

Enrique Zabala

Las Vegas, Rangali Series. A Statement.

Las Vegas is surrounded by a bleak landscape—the Desert—where death is all that can be expected. In Rangali, in the Maldives, this immediate hostility is embodied by the Ocean. Both Las Vegas and Rangali are places where the most dangerous, risk-filled landscape directly borders the most favourable, pleasant environment, designed and built as a place where the vanquishing class can pay for peace of mind, for feeling protected and worry-free, for being without fears, while faced by the unfavourable, and in this case immediate, outer landscape.

Nothing to worry about, nothing to build, nothing to alter, nothing to fight against. Those who pay to cease being alert appear stunned, relaxed. They know they are safe in the eye of the hurricane. In the Maldives, this hurricane’s eye can only be grandiose. The landscape becomes an implausible optical effect by revealing itself as fully analogous to its graphic portrayals in the mass-media and in travel agency brochures. Those who return from a trip to the Maldives do not show any photos—What’s the use? We know the story. The images captured by visitors are a lesson or a demonstration: impossible to approach the subject other than as a post-card, as a photograph from a travel catalogue; no room for anything different, for improvisation or specific interventions; no hidden alleys or unexplored perspectives. Everything is given to us ready-made, definitive and predictable, already built and apparently indestructible. The number of focal points on the island, from which every “noteworthy site” can be seen, is limited and is conditioned by the system of roads and beaches. Nothing to translate, nothing to reformulate, a mirage. Both Rangali and Las Vegas are forgeries, ever-hated by those who miss the outdated criteria of authenticity.

In painting, realism is very easy, and so is the most extreme abstraction. I can reproduce anything, and I can do it very faithfully, as a camera would, avoiding any filter, any improvement or intervention. Despite their position as theoretical extremes, photo-realism and monochrome painting share a ceremonial taste for lethargy, for what is easy, for what doesn’t need to be interpreted or corrected, the mechanical, the industrial, for what turns us into a tool. In those two genres, both the process and the result can only be slushy and sticky, precise, gridded: we know it by heart, we have seen it ad nauseam. We could point to a certain continuity between mechanically painting a copy of a photograph and producing a flat monochrome surface. Two extremes that seem to converge.

I strap my camera around my shoulder, I let it hang by my hip, with a remote shutter release. I play the role of a neurotic, impotent prowler. This is Rangali. The Ocean is a few metres away, in the background, behind an artificial beach, strange and murky like the mossy marble slab of a grave. Here rises the extreme work of man, which feeds on men. There rises the primal landscape, devourer of men. Two extremes copulating. Like the tombstone and the grave. Through the camera lens, my character captures images analogous to those delivered by the ever-unexpected mirror on the column of a shopping mall; images of other bodies, or one’s body, this time immersed in the dialectics of the other, of the double. In those encounters, my character takes on the appearance of somebody who seeks to be liberated from initiative and anxiety, to surrender to the dominance of what is easy, and to be humiliated through the contemplation of the specific fragility of the sterile.

Each painting conceals a bomb behind its stretcher. That’s why I expect the viewer will not feel comfortable. It is not a game, it is not a question of finding anything that may lie in the painting. The paintings in the Maldives series speak the dangerous kitsch language characteristic of the taste of a certain social class. The members of this social class appear on the paintings, they will see themselves reflected like in a mirror, static, like effigies of themselves. The appear relaxed and happy, like a tragic summary. In some way, they don’t know what the non-happy think, their exclusiveness has taken them too far.

I have used two kinds of canvas in this series. One absorbs the paint more than the other, and the former lacks the dazzling white primer of the latter. The least absorbing one forces painting by jerky strokes, while the white primer makes the brush slide in a more flowing manner. I paint mechanically, like a brainless person. I invent games to stay alert, to keep my attention on the canvas during the painting process. I can paint and consider definitively finished some areas the size of a typing sheet of paper, that are far apart, while the rest of the canvas remains empty. I can make a grid on one or two canvases and pretend that I paint the pictures following a geometric pattern. I can paint the canvas like someone who writes a story, from left to right and from top to bottom. Anything to avoid the tremendous anxiety I feel from painting like a machine.

The videos that accompany my series set a course, that of rejecting the present, the course that protects us from our worst fears and makes us follow in the footprints of an uncertain order. My character carries out disciplined crossings, without needing to pause, without intending to penetrate the world, deliberately omitting crossroads and options. They are obsessive hikes, similar to those of Harry Dean Stanton in Paris, Texas, or those of Burt Lancaster in The Swimmer. Animals without a way out, social corpses stripped of any prestige that run away from the need for action, thanks to an excessive task that places them far from turbulence. These strolls always border the danger zone, the Ocean, that no-man’s-land where a naked, persistent immersion would lead to death. The perimeter of Rangali Island can be walked in half an hour, like most of the Maldive Islands. "

Enrique Zabala

.jpg)

.jpg)